Poetry orders the soul. The deliberate meter of language husbands something transcendent within us that makes us remember we belong.

Poetry educates us about the beauty of the world. While in one hand opening the daily existence to the possibility of an expansiveness so great it indicates a divinity just out of view, in the other it can bring a sense of closeness, belonging and place to help us see we are at home in the world. In the old way, students would imitate great language up to the point of habit, until the habit was no longer consciously imitating, and could then support our natural innovativeness. As the Irish saying goes, “Don’t give a man a sword until you’ve taught him to dance.”

The modern desire to radically destroy inheritance seeks to deprive us of our entraining in the rehearsing of great works, of this balancing act whereby dangerous or radical acts of innovation or revolution can be made safe through the prior work of husbanding soulfulness within us. If the sacred is denounced as superstitious or religious, then we are adrift or banished within the illusion of our own peculiar kind of novelty.

We must reclaim a way of rehearsing the sacred. Steeping our hearts in poetry dissolves what post-modern barbarism creates in the form of alienation. It helps us identify a deep reservoir of beauty within us and the world around us that helps us preserve the human ecology of profit making, preserve natural ecology, preserve inheritance, preserve respect for one another lest we fall into nihilistic brutality, and offer each of us individually the sense of possibility that whomever we aspire to become we can become.

The sense of alienation dissipates when we rehearse Beauty. The postmodern instinct claims that it is a failure of our materialist industrial Machenschaft to supply us with spiritual well-being. So we rip down the so-called “patriarchy“ in revenge. Stripped of a sense of interiority, we wear shirts which say “make being black human again.” Without this sense of sovereign interiority, which is a sense of the beauty all around us, we resort to industrial age Machenschaft inhumanities like social engineering. But when we experience an involuntary sense of wonder we are identifying our true stunning worthiness, beauty and excitement reflected in something external. It is proof that who we are is more powerful than anything we can contrive through making chattel of ourselves.

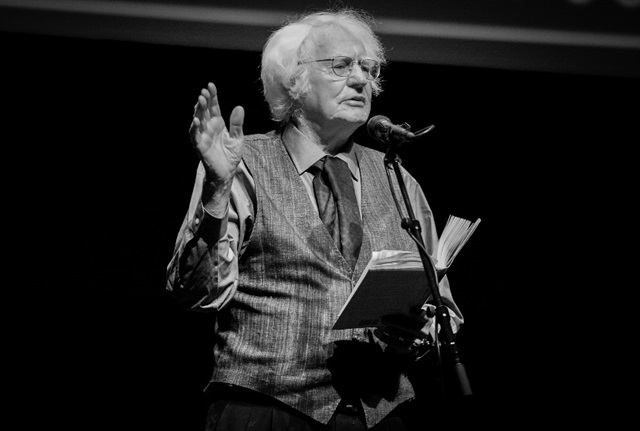

Very gently, Robert Bly helps us see it is not within the power of our earthly fathers, or by some extension a sense of hierarchy, to supply our spiritual well-being, but instead a job we must do ourselves to rehearse beauty and soulfulness so that the original creature within us can be husbanded and loved.

As Bly puts it:

My friends, this body offers to carry us for nothing, as the ocean carries logs.

Sometimes it wails in its great energy, smashing up the rocks, lifting up the crabs that flow around the sides.

There comes a knock at the door, we do not have time to dress.

He wants us to go with him through the blowing and rainy streets, to the dark house,

And there find the father, whom we have never met, who wandered out in a snowstorm the night we were born,

And has lived since longing for his child, whom he saw only once, as he worked

As a shoemaker, as a cattle herder in Australia, as a restaurant cook who painted at night.

When you light the lamp you’ll see him, he is there behind the door, his forehead so heavy, his eyebrows so light, lonely in his whole body, waiting for you.

Robert Frost knew the form was more important than the content. Because it is in the form of poetic language that we rehearse the patterns of beauty all around us. Poetic form is a metaphor in itself. Aristotle said that the power of metaphor could not be taught — that we possess an innate understanding of its power and of the power of symbology. That is to say, we know instinctively about the possibility of a transcendent reunification: The ability to see counterintuitive likenesses which then become intuitive convinces us of the gift of our own being. In this way, poetry is abstraction but it is also nonfiction. Like mythos, the form of good poetry is part of the symbology which points us to our true nature. You can hear this form at work in the German of Rilke’s “You Come and Go:”

Du kommst und gehst

Die Türen fallen wir sanfter zu

Fast ohne wehen

Du bist der Leiseste Von allen

Die durch die leisen Häuser gehen

Man kann sich so an dich gewöhnen

Dass man nicht aus dem Buch schaut

Wenn seine Bilder sich versöhnen

Von deinem Schatten überBlaut

weil dich die Dinge immer tönen,

nur einmal leis und einmal laut

Oft wenn ich dich in Sinnen sehe,

verteilt sich deine Allgestalt:

du gehst wie lauter lichte Rehe.

und ich bin dunkel und bin Wald.

Du bist ein Rad, an dem ich stehe:

von deinen vielen dunklen Achsen

wird immer wieder eine schwer

und dreht sich näher zu mir her,

und meine willigen Werke wachsen

von Wiederkehr zu Wiederkehr.

And in the English:

You come and go. The doors swing closed

ever more gently, almost without a shudder

Of all who move through the quiet houses,

you are the quietest.

We become so accustomed to you,

we no longer look up

when your shadow falls over the book we are reading

and makes it glow. For all things

sing you: at times

we just hear them more clearly.

Often when I imagine you

your wholeness cascades into many shapes.

You run like a herd of luminous deer

and I am dark. I am a forest.

You are a wheel at which I stand,

whose dark spokes sometimes catch me up,

revolve me nearer to the centre.

Then all the work I put my hand to

widens from turn to turn.

In one of his “Love Poems to God”, Rilke here says God is like ”dark spokes which revolve (him) nearer to the center.” Not only is the poem itself laid in elegant form, but says that through an organization of the sacred, everything we do “widens from turn to turn.” We instinctively unify concentric rings of meaning across proportions which make sense in ways we cannot always cognitively articulate. Even the rhyme scheme he uses is not repetitive quatrains which can often be like mini echo chambers. Instead they alternate into sextains which noticeably elongate the rotation of the rhymes in the pattern that a fractal elongates a curve beyond the confines of a circle. The very structure of the poem is a microcosm of a logarithmic expansion which widens from turn to turn.

It is through this subtle tailoring of poetic language that we can rehearse and husband ourselves within the sense that beauty, consolation and a sense of place are all around us. In architecture, it is a similar type of repetition of form through the various proportions of a building which also serve to remind us of a transcendent resonance between who we are and the universe in which we live. This resonance is a kind of lithotripsy against our alienation.

Poetic structure reminds us that the original creature within us can be husbanded and loved. It helps build within us an architecture of meaning that reminds us we are at home in the world, and how we may grow as heroic beings, rather than atrophy in alienation.

-RC